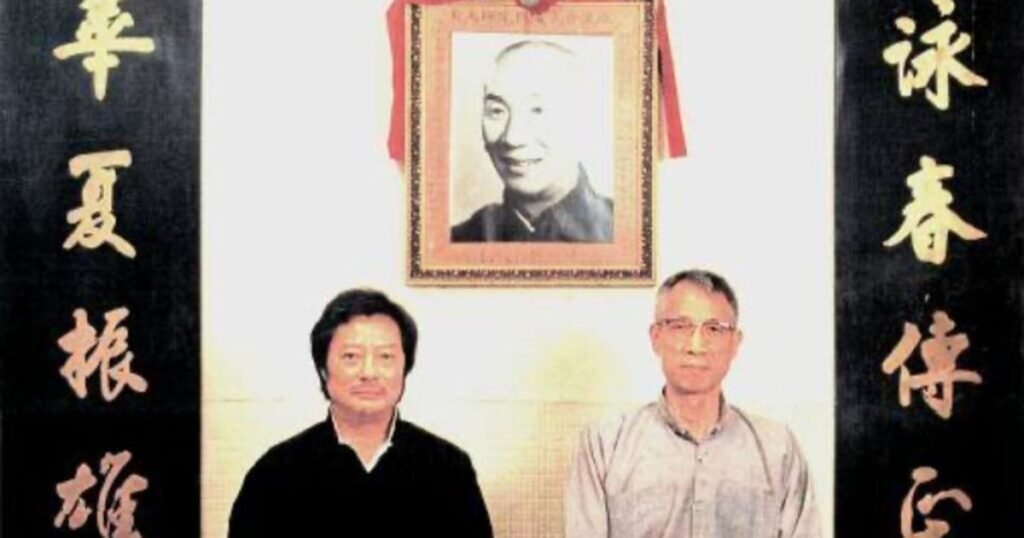

Wing Chun Master Wong Shun Leung was interviewed by ‘Inside Kung Fu’ magazine in 1983. He talked about his Kung Fu life, his fights, Bruce Lee and Ip Man.

“Self-defence is only an illusion, a dark cloak beneath which lurks a razor-sharp dagger waiting to be plunged into the first unwary victim.

Whoever declares that any weapon manufactured today (whether it be a nuclear missile or a hand gun or a blade), is created for self-defence should look a little more closely at his own image in the mirror. Either he is a liar or is deceiving himself. ““Wing Chun Kung Fu is a very sophisticated weapon; nothing else. It is a science of combat, the intent of which is the total incapacitation of an opponent. It is straightforward, efficient and deadly. If you’re looking to learn self-defence, don’t study Wing Chun Kung Fu. It would be better for you to master the art of invisibility.”

Master Wong Shun Leung

Rather peculiar words, you might say, coming from an individual who’d spent over 30 years of his life teaching kung fu; yet somehow there’s a rather uncanny philosophical depth to the man who actually instructed Bruce Lee in Wing Chun Kung Fu and inspired William Cheung to enter Ip Man’s school at the age of 13. Wong Shun Leung, one of the most senior phenomenon in Wing Chun today, earned his rank and title where it really counts – in the streets.

Now, at 48 years of age, he’s still far from being a pacifist. With a series of jagged scars along his knuckles and a piercing glare in his eyes, he gives the distinct impression that he’s already witnessed a fair share of human folly and its consequences. With the wisdom of a veteran, he guided us through a period in Hong Kong’s recent past where fame flew like the wind before a fist as Wing Chun Kung Fu became a household word.

Early Years of Master Wong

Born in Hong Kong on 8 May 1935 the eldest son of a Cantonese traditionalist doctor, Wong Shun Leung grew up in the hard world of broken bones, bruises, poultices, and amidst shelves of herbal medicines that had been devised over thousands of years to remedy internal injuries of every kind. As a child he was exposed to fantastic legends of almost superhuman men who controlled and used their bodies like fierce weapons and always against innumerable odds. And because his father was well acquainted with the local kung fu community, Wong would find himself encountering a fair cross section of Hong Kong’s warrior elite and wondering just how powerful and skilful they really were.

His curiosity and interest in the both Kung Fu and other Martial Arts, in fact, grew almost on a daily basis. By the time he was eight years old, he could be found sitting in the dark corner of some local cinema watching the last vestiges of silent kung fu movies. To add impact to Wong’s already blossoming imagination, his grandfather just happened to be a very close friend of Chan Wah Shan, the first of Yip Man’s Wing Chun teachers. Both grandfather and father would describe in detail Chan’s martial prowess, especially in one particular incident when Chan was already an old man, he publicly defeated a fierce young fighter in Fu Shan.

Master Wong’s Favourite Hobby

As fate would have it, Wong Shun Leung soon discovered his first and most favourite hobby, fighting. School became somewhat a boring proposition for the young Wong, so he began frequenting various isolated locations such as the tall apartment complex rooftops and secluded parking lots in Hong Kong, where extracurricular activities could be carried out without interference from the police. Here most local vendettas, gang warfare and personal grievances were settled with a sense of privacy. These duels were not without a sense of honour, however, and Wong quickly learned the rule of etiquette involved, hit first, ask questions later. As his skills began to improve, he developed relationships with a number of martial arts students who eventually convinced him to study formally.

Between the ages of 15 and 16, Wong tried a number of Kung Fu styles and settled first on Tai Chi Chuen, then eventually on Western boxing. He liked boxing the most, because he considered it most practical for street warfare. He found an instructor and began working out in a gym regularly.

Unfortunately, a day came when Wong accidentally socked his coach a bit too hard in the face. The coach, infuriated, proceeded to pound Wong into a pulp. Bleeding from both nose and mouth, he then managed to corner his coach and knocked him out stone cold. From that day on there were no more boxing lessons, Wong had lost respect for his teacher.

Master Wong and Ip Man

Wing Chun, at that time, was a relatively unknown style of Kung Fu and as Ip Man was the only known teacher, Wong had never had an opportunity to witness a real Wing Chun fighter. However one day his cousin introduced him to Ao Yuing Ming, one of Ip Man’s junior students. Ao was about 30 to have a match with a southern praying mantis stylist named Law Bing.

Although Ao was much younger, weaker, and less experienced than Law, it became evident to everyone present that Ao’s martial art was technically much superior. By the time Law had driven his opponent to the edge of the balcony, he himself had already decided to study Wing Chun Kung Fu. The match ended peacefully and Ip Man had a new student. Wong, however, was still quite sceptical of this new Kung Fu system until he by chance observed one of Ip’s senior students, Lok Yiu, toy with a northern praying mantis stylist named Lam. Lok Yiu was so skilled that he seemed to be making a joke out of the whole event. This impressed Wong enough to incite his curiosity further; he wanted to meet Ip Man.

During the third day of the lunar new year celebration when most of Hong Kong remains at home, Wong, then only 17 years old, went in search of his next door neighbour, who was none other than Law Bing, at Ip Man’s studio. Law was absent, but there were a few junior students practising Chi Sau (sticky hands). Wong’s first impression of this method of training was far from flattering. To him it was an impractical form of movement that limited a fighter’s capability to withstand any attack that didn’t come head-on, face-to face. He made the ultimate error in any Martial Art circle by scoffing at the style itself, comparing it unfavourably to the sophistication of Western boxing.

Ip Man and Wong’s Dispute

Ip Man was quietly observing. As could well be expected, one of the students challenged Wong. It turned out to be a short but sweet encounter. Wong’s opponent hit the deck in a matter of seconds. Ip, becoming somewhat upset, asked If Wong would like to try one of his more senior students, his own nephew for instance. Wong agreed. This time his opponent was a much more serious fighter, but Wong still managed to throw him around the gym like a rag doll.

Ip, by now raging inside with all the insult Wong had afforded him, suggested that perhaps Wong might consider trying him on for size. Recollecting the last incident with his own boxing coach and noticing that Ip appeared pretty much over the hill in comparison (Ip Man was 56 years old). Wong decided that this match was going to be a real “pushover”. Even though Ip had very large hands and strong forearms, Wong felt that he could easily tire out this thin old man by using some fancy footwork and moving around him.

Ip was by far the greater strategist. He carefully manoeuvred his opponent into a corner and just when Wong was halfway through a kick to the midsection, Ip pushed him on the chest knocking him, off balance, into the wall. Ip quickly closed the gap and executed a rapid-fire six to seven blows into Wong’s body just hard enough to let him know that he could have done real damage if he had wanted to. Wong was amazed at Ip’s speed and control. He knew he had found a master at last and asked permission to study with Ip Man.

Wong Shun Leung vs Yip Bo Chung

Ip, however, felt that Wong was not really sincere in his request and was just about to refuse him when a much senior student, by the name of Yip Bo Chung, arrived. Bo Chung was in his mid-30s, five-foot-ten inches tall, and as strong as an ox. Everyone had named him “Big Scrub-brush” because he was so proud of himself that they felt he could wear down an opponent with his boasting alone. Here was a newcomer for him to test his skills upon; so he decided to square off with Wong.

This time Wong was going to get run through the washing machine. Bo Chung punched and kicked the daylights out of him. Not one to be discouraged however, Wong, on the eighth day of that same lunar new year, formally submitted himself as one of Ip Man’s students. One day during practice Wong overheard Ip Man in conversation with his most senior student, Leung Sheung, during which he stated that he felt the “kid” (Wong) would probably, in a year’s time, make a name for Wing Chun Kung Fu in Hong Kong.

Wong becoming Famous in Hong Kong

The prophecy turned out to be incorrect. It didn’t take Wong a year, it took him three months. Weighing in at slightly over 105 pounds, Wong turned to some serious “scrapping.” No holds barred, he took on every challenger and beat them into the dust. He developed such a bad reputation as a scrapper that people nicknamed him the “Flying Soot”, a type of filth that results from a fast fire and manages to stick something dirty on you when least expected.

Wong’s enemies were not few and far between either. After demolishing a foreman in the Public Works Department by the name of Wong Kiu, he found himself confronted by a whole group of challengers, most of them reputedly paid by Wong Kiu. Finally the number of people willing to fight him, even for money, diminished into nothingness. Between the ages of 18 and 19, Wong had fought over 50 bouts, most against opponents larger and stronger than himself, and had come out the victor.

Suddenly Wing Chun shot into the forefront of Hong Kong’s Kung Fu gossip. Here was a style that really achieved results! Cheung, then a chief detective in the Royal Hong Kong Police’s Criminal Investigation Department, had a number of sons who were being tutored in the martial arts by a varied group of teachers. The oldest son, Kong, was a swimming partner of Wong Shun Leung’s younger brother. So when Kong’s Kung Fu instructor decided it would be in the boy’s best interest to leave the Southern Chinese “four styles” system and take up Wing Chun, it was only natural for him to go to Wong Shun Leung. Kong was a sceptic, so the two of them decided to have a match. Wong had very little trouble in the fight though, so Kong became convinced that Wing Chun was his next step.

Wong Shun Leung and William Cheung

One day, as the two of them were practising Siu Nim Tao (the first pattern of the Wing Chun system) in Kong’s garden, Wong started to demonstrate the proper formation and use of a block called tan sau which involves stretching the arm out toward your opponent, palm-up. Suddenly a voice shouted from above then “Oh, so you want a handout? I’ll give you 20 cents for that!”

Both men looked up and saw a tall young boy standing on the balcony watching them. Wong asked the name of his new audience, so William Cheung, Kong’s younger brother, was formally introduced.

“Does he practice any type of Kung Fu?” asked Wong. “Yes, and he really likes to fight,” said Kong in reply. Wong asked William if he wanted a match, whereupon William, smiling, rolled up the sleeves of his Chinese jacket and came right down. It wasn’t really much of a contest because, as Wong knew, the boy was only about 13 years old, seven years his junior; but there was a special quality about William.

He was extremely fierce, for one thing, for a boy of his age. He wanted to take up the study of Wing Chun immediately, but as his brother opposed it William had to wait. Kong was afraid that if his younger brother learned Wing Chun he would be very hard to control. As it was, William already had a bad reputation for fighting and was said even to use weapons if necessary. His father had already suffered too many headaches as a result.

The day came when Kong left for Australia. William lost almost no time in attending Ip Man’s classes. He learned very quickly, and before long he was seen following Wong’s footsteps as a local Wing Chun Kung Fu terrorist! Somehow, during this time, William had developed a close relationship with another boy of his own age. They would often go out on fights together, and one day, William brought his friend into Ip Man’s school.

Wong Shun Leung’s First Encounter with Bruce Lee

That’s the first time Wong Shun Leung ever saw Bruce Lee. Wong noticed that as Bruce began to study Wing Chun, he didn’t really seem all that sincere; consequently his progress was slow. He also had a tendency toward laziness, Wong felt, and whenever he got into trouble with an opponent or the law he would depend on either William or his father’s police connections to bail him out. Bruce always looked up to William as a fighter, and when William left for Australia at the age of 18, Bruce found himself suddenly alone and stranded in a hostile environment. It was then that he turned to Wong Shun Leung and started to take Wing Chun seriously.

During the time of Bruce’s enrolment at the St. Francis Assisi Secondary School in Sham Shui Po, he had managed to talk a number of his classmates into learning Wing chun. But as Bruce began to have a change of heart toward his own training, he tried to find a method of cutting deeper into Wong’s class time. He approached Wong one day and asked for private tutorship; but when Wong refused, Bruce found an alternate solution. He would run over to Wong’s house after school in advance of his classmates. When they arrived for practice they would find Lee sitting on the steps looking rather disappointed. He would claim that Wong was not present, so they’d all leave together. Not long after, Lee would return and get his private lessons with little hindrance.

Bruce Lee studied almost every day with Wong for a period of one and a half years. During this time he proved to be a very clever and innovative student. Wong felt that Lee’s strongest point lay in his chi sau practice. He had begun to develop his reflexes to such a degree that he was able to respond instantaneously to just about any force applied by an opponent’s attack. Lee would have continued with Wong for quite a longer period but fate would have it that his complicated lifestyle and attraction, for fighting forced his parents to send him overseas to study. From that point on, barring occasional visits by Lee to Hong Kong either for filming or to see his parents, Wong’s relationship with Lee was carried on through the mail.

Bruce Lee Creation of Jeet Kune Do

When Bruce first started teaching Wing Chun in the States he would often write to Wong to clarify certain technical aspects of the style. As he continued to develop in his martial abilities and throughout the creation of Jeet Kune Do, Lee kept Wong well informed of his theories and progress. Wong Shun Leung was the type of man Lee could relate to. He was a true fighter with an analytical approach to the Martial arts.

When Lee finally did arrive in Hong Kong, he would visit Wong and the two men would talk theory and technique for seven or eight hours a day. It was during one of these marathon discussions, just prior to Lee’s death, that Bruce said he felt perhaps he should never have started Jeet Kune Do. When Wong asked him why, Lee explained that although in theory KJD was an advanced system of combat, in practice it didn’t seem to work because it was too difficult for a teacher to teach the somewhat abstract style to a number of students with varying capacities and expect them not to become confused.

Bruce Lee himself had learned in a traditional way. He first fought in the streets to gain experience and then tried to develop his own experience and ideas into a new format. He had learned all the elements of chi sao, but it was difficult to base his new teachings strictly on Wing Chun Kung Fu. A link in the chain was missing. Wong suggested that perhaps Bruce was trying to cover too much ground in too short a period of time. But on the other hand, Wong agreed absolutely with Lee’s analytical approach to combat. In order to keep abreast of the times, he too felt that one should not always accept what is being served without testing its validity.

Today Wong, like Bruce Lee, is innovative in his thoughts. Although he appears to teach in a very authoritarian and traditional way, upon deeper inspection he’s very ready and willing to advise and elucidate any queries a student might have. He also believes in teaching Westerners, which is in direct opposition to the mandates of Ip Man.

Chinese Kung Fu and the Western World

Traditionally, Chinese Kung Fu masters refused to accept Western students due to two factors one, hostility still remaining from the Boxer Rebellion and two, the fact that most Westerners are much larger and stronger than the average Chinese. (It would be quite logical to assume that, given his size advantage, if a Westerner were to have the same level of expertise in kung fu he would be able to defeat Chinese opponents.) But Wong insists that a good student, regardless of race or creed, is still an honour to his teacher. Sometimes the least expected student becomes the most outstanding. It is the duty of the teacher, he feels, to give everyone who so desires a fair chance. Wong explained to us some of the twists that fate had brought to the Wing Chun Kung Fu system in the past.

Dr. Leung Jan was a renowned martial artist and excellent combatant during the earliest recorded years of Wing Chun Kung Fu’s history; however his eldest son did not have the capacity to carry on the style’s fighting tradition. This task was therefore allotted to Leung Jan’s most outstanding student, Chan Wah Shun. But although Chan was a fierce scrapper, he lacked the necessary intelligence to analyse his own style in detail.

In this way Leung Bik, Leung Jan’s eldest son, was superior. He was well-educated and could distinguish the chaff from the wheat. But when both men later went into the bone doctoring business, Leung Bik found Chan was a powerful competitor who not only netted most of the available students, but most of the local patients as well. Chan also managed to relate to the local townspeople of Fo Shan better than Leung, so Leung left for Hong Kong and became a silk merchant.

Ip Man and Wing Chun Kung Fu

Ip Man studied under Chan Wah Shun for two years until Chan’s death. After that he continued his studies under Ng Chung So, one of Chan’s senior students, until an incident occurred in which Ip Man, only 16 years old, killed someone in a fight. As his parents were very wealthy they were able to transfer Ip almost immediately to Japan in order to avoid any further difficulties with the authorities. He later travelled to Hong Kong and began attending the St. Stephan’s school for boys.

Ip was a real troublemaker. He would fight almost constantly and even upon occasion beat up the school’s Indian doorman. One day, one of his classmates suggested that perhaps Ip wouldn’t mind matching fists with a Wing Chun teacher. Ip agreed and soon found himself face to face with an elderly man. Much to Ip’s surprise the old fellow defeated him with relative ease. Ip asked to join the man’s classes and found out that his new teacher was none other than Leung Bik.

Leung was very clever and analytical as a teacher, which impressed Ip very much. Thus, eventually Ip Man became the product of two masters, one a better fighter and the other a better teacher. Regardless of who Ip learned most from, Wong feels today that Ip Man’s own admirable qualities, both his martial proficiency and his cleverness, more than indicated something about the man.

Since the deaths of both Ip Man and Bruce Lee, Wing Chun Kung Fu has gone through quite a number of changes. Whenever any particular style becomes popular, it’s bound to attract those who seek fame and fortune. Wong Shun Leung is somewhat of a purist in this respect. He realises that a style’s popularity will often redirect some of the original theories into new avenues, but he sincerely hopes that the original precepts are clearly understood by all who wish to alter them.

Wing Chun Kung Fu Explained by Master Wong Shun Leung

In that way perhaps the best ingredients may not be lost in the process. It was for this reason that he agreed to demonstrate some of Wing Chun’s basic techniques and theories on a videotape entitled Wing Chun – The Science of In-Fighting. Theory, on the other hand, can go through levels ,that even video may not be able to capture. When asked about some of the more important aspects of Wing Chun Kung Fu, Wong was able to explain the following:

Wing Chun is the science of using the right amount of force at the right time in overcoming an opponent. Using the least amount of energy to accomplish this goal means that one is economising motion. The basic premise of Wing Chun Kung Fu, therefore, is the economy of motion.

Wing Chun Punch

To begin with, according to Wong, the style’s primary strike is a punch in which the hand and forearm are curved slightly upward upon impact. There’s a very good reason behind this motion, which few practitioners really understand A straight-hand punch allows the force of an opponent’s body to travel back along the arm and into your body, thereby causing a certain amount of instability and reducing reaction time by just a fraction of a second. The wing chun punch, on the other hand, creates another outlet for the opponent’s force down along the angle of one’s wrist toward the ground. In this way one can hit as hard as one likes as long as the timing is correct.

Chi Sau

Chi Sau is a prime example of economy in motion, Wong says. According to Newton’s law of inertia, a body will stay at rest unless it is acted upon by an outside force, and once in motion will remain in motion until opposed by an outside force. Combat involves a series of high-speed movements, the forces of which act upon one another. During some of these movements, such as a block for instance, the opponent will forcefully displace your arm in a direction away from your intended target. It will take you a few microseconds at least to get your arm back in the proper alignment to attack.

Chi Sau teaches you how to overcome such inertia so that your attack never wavers an inch from its decided path. It is a very difficult practice to master, but after years of training it is said to develop both elasticity and softness in your muscles as well as a tremendous control over reflexes.

Constant chi sao practice also teaches strategy. You begin to feel a pattern in your opponent’s movements, allowing you to sense the proper angle of attack. According Wong, the highest achievement Wing Chun Kung Fu is to be able to allow your opponent to guide you into the exact method of attacking and defeating him.

Some Western pugilists might claim, pretty much as Wong did when he first entered Ip man’s gym, then chi sau would be useless against an expert Western boxer. Wong himself now feels that most boxers, by using a leading stance, are allowing the reverse arms to be at a disadvantage due to an increased distance from the opponent. The jab is fast and efficient but it must still come within range to be effective. This is where the Wing Chun man moves in. Once inside a boxer’s inner circle, chi sau methods match two hands to one. As a result of this slight inadequacy many boxers have altered their stances to confront opponents in a more head- on fashion. Finally, at very close range, where most styles eventually resort to grappling, Wing Chun attacks become much more efficient.

Wooden Dummy

Many Kung Fu practitioners look upon the wooden dummy as an ideal way of toughening up the hands and forearms, and nothing more. Wong reminds us that although it is made of a hard substance, it still represents a man with arms and legs. The purpose of the dummy is to develop proper timing in an attack, that is, to intensify one’s ability to block and punch both at the proper angle and simultaneously. The premise of the dummy is continuity. A teacher can distinguish a student’s progress by just listening to him or her practice on it. The sounds alone indicate whether a student has developed the proper co-ordination and technique necessary for learning the higher Wing Chun Kung Fu’s functions. If your angling, speed, stance, or pattern is wrong, a good teacher can correct you almost blindfolded. Once again, economy of motion is the name of the game.

Footwork in Wing Chun

There is some contention as to whether Wing Chun Kung Fu has developed any footwork or not. This is due to a false conception resulting from two factors: one, very few Wing Chun practitioners stayed with any master long enough to learn the footwork; and two, most matches involving Wing Chun were decided without the need for footwork.

According to Wong, there is no logical or practical reason for teaching a student advanced footwork until he’s already mastered hand techniques. The reason, he feels, is that the hands are able to continue in motion with little effect on one’s general stability; but when the leg has left the ground, it must eventually return to the ground, otherwise the advantage is strictly the opponent’s. In order to maintain stability, the legs must be confined to attacks below the waist. Wing Chun has basically eight leg strikes, which are all tailored to speed and efficiency.

There are two primary footwork patterns used to control one’s distancing, but what few people realise is that wing chun also has a form of chi sao created strictly for the legs, called ‘Chi gerk’. There are a fewer number of techniques involved, but the theory is the same as for the hands. Most Wing Chun practitioners have had little exposure to these techniques.

The Wing Chun Weapons

Even less well known is the practice of Wing chun Kung Fu’s weaponry (such as the double sword and long staff). There are a very limited number of qualified weapons teachers in the world today, probably because weapons have always been the last on every master’s teaching agenda. Wong says he will eventually demonstrate these forms on another videotape, but he is reluctant to have students attempt weaponry prior to mastering the Wing Chun hand and leg patterns.

His reasoning is quite logical. A weapon may be considered an extension of the hand, but unlike the hand which can, by pushing or pulling, control an opponent’s distancing or force, a weapon is limited by weight and structure. By studying weaponry too early, the student will either lose or alter his concepts of distancing, speed, and control. His overall stability, stance and footwork will suffer as a result. If he cannot control his own movement without an object in his hands, then how can he expect the object to assist him in any way? Wong feels that any teacher who suggests learning weaponry prior to mastery of the other Wing Chun forms should reconsider his own intentions.

Wong Shun Leung

Wong Shun Leung is an appropriate example of a man who has become his art and vice-versa. He started as a gifted fighter, studied both the physical and mental aspects of this system Kung Fu, and finally became Wing Chun spiritually. He’s a man who can be either soft-spoken or outspoken depending upon the situation at hand. He has learned to understand his own limitations and thereby the limitations of others. His demeanour is calm, relaxed, and his intent unwavering. He is philosophy without embellishment, like an old sword that doesn’t appear dangerous at first, until you’ve tasted its razor edge!

An article published in ‘Inside Kung Fu’ magazine. Modified by Mindful Wing Chun Online.